New Study: Limiting Sugar Consumption In Utero and in Childhood Prevents Chronic Diseases Later in Life

By Tracy Beanz & Michelle Edwards

A mother’s nutrition during pregnancy and her child’s nutrition in the first two years of life (the first 1000 days from conception to age two) are crucial elements in a child’s neurodevelopment and lifelong mental health. Why? Because child and adult health risks, including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, are programmed by nutritional quality during this critical period. With that in mind, a new study has confirmed that a low-sugar diet during this timeframe can significantly reduce the risk of chronic diseases in adulthood. Indeed, the adverse and lifelong effects of too much sugar consumption for both pregnant women and young children are profound.

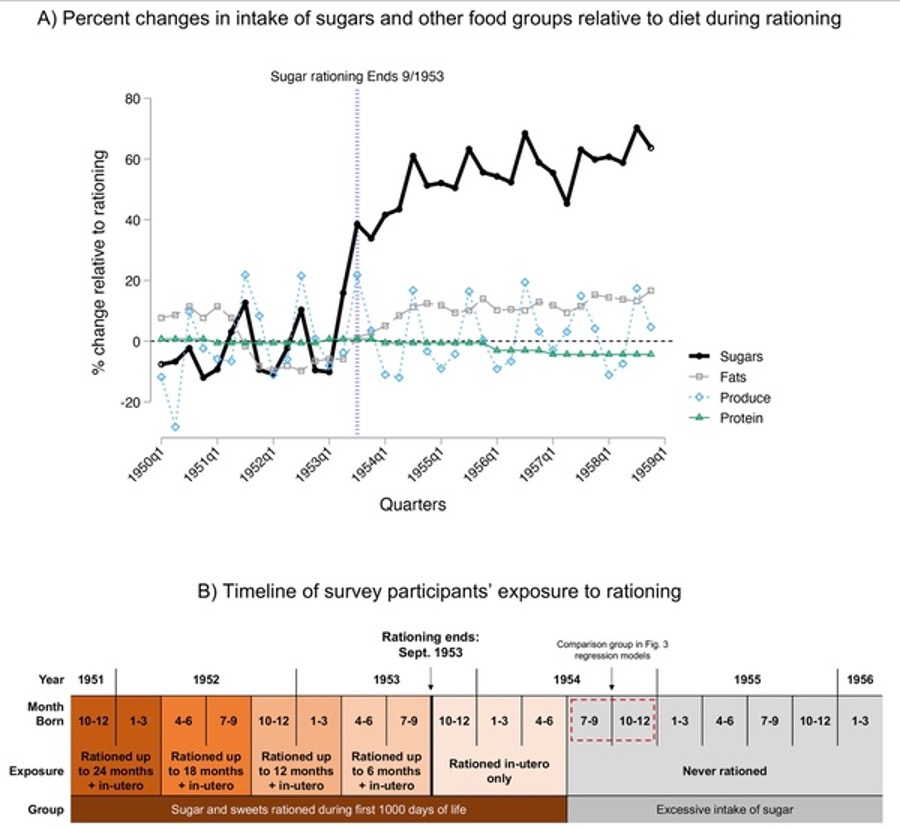

The study, titled “Exposure to sugar rationing in the first 1000 days of life protected against chronic disease,” was released on October 31, 2024. It used the natural experiment of post-World War II sugar rationing in the United Kingdom to obtain its data. During rationing, which lasted a decade and ended in September 1953, sugar intake in pregnant women and young children was restricted due to ongoing economic challenges, supply chain interruptions resulting from severely disrupted global trade and shipping routes, and the need to manage limited resources. Sugar was a commodity primarily imported from sugar-producing regions in the Caribbean and other parts of the British Empire and was more challenging to acquire in sufficient quantities. Shortages persisted even after the war ended.

The study found that early-life rationing of sugar reduced diabetes and hypertension risk by about 35% and 20%, respectively, noting that “current dietary guidelines recommend zero added sugars” during the first 1000 days since conception. Great advice, yet we know that is not the case in the United States, where unhealthiness prevails. Thus, not surprisingly, the study added, “but, in the United States (US), the majority of children are exposed to excessive sugar through maternal diet in utero and while breastfeeding, and directly by consuming infant formula and solids.” Highlighting the sugar problem in the US, the study explained:

“Pregnant and lactating women, on average, consume more than triple the recommended amount of added sugars, surpassing 80 g per day, and most infants and toddlers consume sweetened foods and beverages daily.”

When rationing was taking place—which, by the way, didn’t involve unnecessary food deprivation—the sugar allowance for everyone in the UK, including pregnant women and children, was roughly the same as today’s dietary guidelines, which are about eight teaspoons of sugar a day for adults, five teaspoons of sugar a day for children, and zero sugar for children under two years old. Regardless, eight teaspoons and five teaspoons is a lot of sugar, but clearly barely makes a dent in the amount of sugar Americans consume daily.

Tellingly, when the rationing ended in 1953, the UK saw an immediate “nearly two-fold increase in the consumption of sugar and sweets” but not in other foods. This scenario created a compelling “natural” experiment. Depending on whether they were conceived or born before or after September 1953, individuals were exposed to varying levels of sugar intake early in life. Those conceived or born just before the end of rationing experienced sugar-scarce conditions compared to those born just after the end of rationing who were born into a more sugar-rich environment.

The researchers, from the McGill University in Montreal and the University of California, Berkeley, used data going back 50 years prior in the UK Biobank to identify those born during the timeframe of the rationing, allowing them to compare midlife health outcomes of otherwise similar birth cohorts. Notably, exposure to sugar limitations in utero alone was enough to reduce health risks. Still, disease protection increased post-birth once solids were likely introduced, which often occurred around six months. The implication of this outcome is significant as it can save costs, extend life expectancy, and, most importantly, improve quality of life, the researchers stated.

Scientists have known for years that sugar is highly addictive. We’ve previously written that, despite being in almost all products consumed today, the human body needs no added sugars—meaning those that aren’t naturally occurring—to survive. Why in the world would we entertain at all the idea of giving any added sugar to our babies, whether in utero or after birth? It makes no sense. The physiological impact of consuming high levels of sugar during the first 1000 days can and will disrupt metabolic programming in a child. This period is crucial for developing numerous bodily systems. High sugar intake can predispose a human life to insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, which are precursors to diabetes.

Moreover, high sugar exposure in infants and toddlers can create a strong, potentially lifelong preference for sweet foods, making children more likely to consume high-sugar diets in adulthood. The study pointed out that sugar exposure beyond gestation—especially postnatally—was linked to a more robust taste for sweetness, perpetuating high sugar intake across the lifespan. In other words, it is an addictive response to sugar. This response is more prominent in women, potentially increasing lifelong sugar cravings and elevating the risk of obesity and metabolic diseases. Bad news all the way around for mothers and their children, who become lifelong customers for Big Pharma. We are hopeful that one day—perhaps very, very soon—this madness will end once and for all.